river

The first thing I noticed was lack—the lack of noise seemed to be a noise in itself, a pressure on my ears. For a while we would walk in the park totally bereft of human presence, excepting that of ours, he and I the only inhabitants of Earth, which for all its splendor does not even have its own light.

As we walked along the bank, all the rivers I had known in my life merged into one. The Han River bisecting Seoul like a smile;

the confluence of the Monongahela and Allegheny Rivers, two names which bewildered me as a child and still do;

and now the █████ on its meandering way towards the Atlantic.

At the site of large rivers and their parks, there is always a wooden pole marked by the heights of historic floods where the river had engorged itself on precipitation, sweeping away all in its path as if possessed by demons. After disasters like these, what remained was likely only the pole itself: the dutiful recording of natural destruction, and a reminder (to no one) of how quickly everything can be lost.

He remained ahead of me with easy strides, as if he knew this place. My cicerone. The sunlight rendered his dark hair iridescent. Its glow split into a diaphanous array of the softest colors, what Newton named “spectrum”, after ghosts. In this way one of the greatest scientists of mankind acknowledged and admitted the mystery underlying all of our world.

Angel, as you know, means “messenger”. In Korean, the literal translation is “sky agent”, homophonic with the number one-thousand-and-four.

The 13th century was a time in which physics was commensurate with angelology; the study of forces which were rationalised as invisible angelic intelligences. Even demons made appearances all across the sciences, which follows quite plainly from the fact that the set of all demons is a subset of all angels. The most famous of them is likely Maxwell’s demon in physics, but there is also Laplace’s omnipotent demon and Searle’s demon which sits forever in the Chinese room. In computers, a daemon is a program which runs tirelessly in the background and does not communicate with the user.

The Rabbinic literature says this about angels:

One angel does not perform two things, and two angels do not perform one thing. […] Thus anything which executes a command is an angel.

So: photosynthesis, gravity, magnetism. Peristalsis, centripetal force, condensation. These are all angels.1

I mentioned this to my friend, whose name is Ángel. He replied with something along the lines of: “Then angels are in line with certain tenets of software: ‘do one thing, and do it well’”. I thought of the researchers at Bell Labs in the seventies, consorting with angels, coaxing them into hulking, turtle-headed machines, which eventually became the svelte metallic rectangles that we carry everywhere in our briefcases and backpacks today.

What Ángel really said was that “angels follow the UNIX philosophy”, only notable because not many things do.

From time to time it strikes me that the people of the Middle Ages were better equipped to deal with our present than we ourselves are today. We rebuke the unseen even as so many of us take its voice, seemingly without origin, for granted. Algorithms are ghosts in the machine that tell us what to watch, read, and listen to. As an inversion of angels, they seem to do, or at least are conscripted to do everything, and yes, the hope implicit in it all is that they will one day indeed be capable of doing anything, and thus save us from our helpless selves.

We sat on a rock jutting out of the river’s shallows. The current could not quite reach between the outcroppings of stone. The rock itself admitted a fantastic and infinitely detailed palimpsest of colour: bands of warm, rusty browns alternating with cool, almost blue, grey. Having worn slippers, I immersed my feet into these stagnant pools. At first the coolness of the water was refreshing, but it soon became almost painful as it chilled me to the bone. I lost feeling in my toes. The silt that had settled and clung to the rock made its underwater surface unbearably slippery. Everytime my foot brushed against the rock, it loosed a cloud of this silt, until only the spot of clarity that remained was in the way white blots of sunlight danced over the water’s surface, condensing in a thick, brilliant streak often called “lichtweg”, literally “light-road”, by plein-air painters.

As I recall it now this scene is drenched in the hazy light unique to memory; its edges are already dark and frayed. This is expected: the mind is not sterile. It is damp and nourished by ceaseless experience. Memories constantly rub against each other, like milling farm animals in various states of living decay. But somehow their decaying only makes them more fecund. A loaf of bread or a piece of fruit strikes me as a (formerly) living thing only when it exhibits its first signs of rot.

Heraclitus called the month a generation, owing to the mathematical robustness of the number 30. By summer I will have spent five generations with him, every single one of which has passed with the pure mercilessness of geological time. In public, I was almost too scared to hold his hand. When we first befriended each other we would communicate solely via texts and scrawls on scrap paper, unwilling to use our voices.

The most beautiful instantiations of poetry I’ve experienced were during mathematics lectures, when gauzy connotation and the hard edge of pedantry fell into syzygy, and I heard a word or phrase as I had never heard it before. “We derive a witness that only testifies to what is true”.

The set of all real numbers between 0 and 1 are uncountably infinite: a smooth, impenetrable surface that admits no gap whatsoever, an impossible object which seems as if it could have been engineered by some civilization of the distant future and fallen into our hands by happenstance. And yet Bernard Bolzano, a man of God, was one of many mathematicians who understood the continuity of the reals as his time approached the twilight of the 18th century.

I was to the left of him. He sat with his back to me. His white shirt shines now like a flag against the ink-blot of my imagination. The sun, unimpeded by cloud cover, shone oblique across our faces. I could not bear to look at him directly.

We walked through the forest trail, which had no clear beginning nor end. The trees around us were skeletons; the only extant leaves were the ones blanketing the floor.

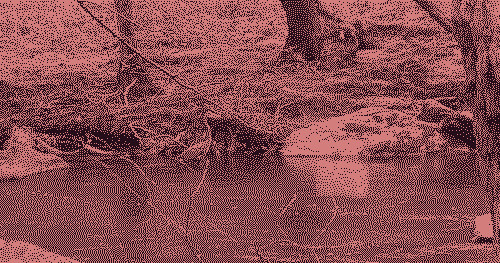

But without any warning, the trees disappeared before us. It was as if an immense scythe, whose handle alone must be a half-mile long, had carved a furrow into the earth. The air was a few degrees warmer than it had been under the canopy, only heightening the impression that we had intruded onto a world hidden from human purview, presumably for good reason. It remains one of the most unreal moments of my life and the picture below does nothing to communicate the unreality.

Bertrand Russell understood well the paradox of induction. His turkey thinks that he is safe and happily goes on living, but encounters an unpleasant surprise on a certain Thanksgiving. Seeing birds, I am without fail reminded of their dinosaur ancestors. They are said to have nearly identical hipbones.

A lattice of tree roots seemed specially engineered to optimize for tripping and falling. I felt uneasy treading on the exposed tracts of a circulatory system which supported lifeforms surely older than my parents, and perhaps even their own parents. The trail constantly degenerated into rocks not yet smoothed by enough pedestrians, rain, and wind, and liable to roll underfoot. Your ankle had no choice but to roll along with it. I was exercising parts of my brain that had not been used for a long time—namely, whatever makes the split-second decision between a sufficiently stable or unstable foothold. (Often, I was wrong.) But he seemed to have no such concerns in his head. That is, every step came naturally to him. My mountain goat. His shoes made no sound.

In literature, there is often reference to babbling brooks and the murmur of streams. But as I observed, the river did not manage anything quieter than a constant roar, totally without hiatus. Eventually the roar receded in its uniformity and became indistinguishable from what I would, quite wrongly, call silence.

In my recollections, and even as I observe him in the present, it seems as if he is on the verge of departure. Once, he admitted to me that he dreamt of my sudden move to another country, after which we would be separated by thousands of kilometres of land and sea.

His is the spirit of a sighthound, mustelid, or ungulate having temporarily found purchase in a human body, and mildly embarassed to be seen in such an ungainly mode. My gaze is an attrition on him. We seem to live among hyperobjects in the process of disintegration, the sinter of sand, chalk, loess, and other by-products of unceasing aeolian processes. Nothing is whole.

In cosmogonies around the world, men are often said to have been created from mud and dirt—but my man is a man of dust. As I approach him I always expect for there to be a pane of spectator’s glass separating us—whether it is he or I who is doing more of the watching, as if there is a way to measure such a thing, will forever be a matter of mystery.