quincunx

About S, well, I love him and all I wish for him is happiness. If I could make it so that he will always feel loved and cared for, for the rest of his life, then I would do that in a heartbeat. I've never felt so much love for someone not directly blood-related to me, and everytime I see him it's as if these feelings only deepen, although I've known him for nearly nine years now.

And these days, getting to breathe in the smell of his shampoo, to embrace him—well, these are the things that keep me from ending it, as it crosses my mind every time I walk across the highway overpass. Sometimes I just want to stand in the middle and watch the cars go by under me. To the left, I see the white headlights of oncoming cars, and to the right, I see the red rearlights of cars receding from view, a toy schematic of the redshift and blueshift demonstrated by the stars of our universe. But I won't do it. Rest assured I won't do it.

He's so important to me. I want to spend the rest of my life with him. (As I write this admission, my eyes momentarily warm with tears.) I almost wish my feelings for him weren't so intense, still; it's almost enough to make me wish, even for a split second, that we had never met.

It seems that I can't experience happiness with S without its dark twin, a sort of premature grief.

Saturday well after sunset, he texted me. I was late in responding; I had been in the shower. I said sorry; he did not respond. He wrote, it's cold out. I checked the weather, it said twenty degrees.For the Americans reading this: a balmy 68 degrees Fahrenheit. Why would he lie to me, I thought. My hair dripped onto my sweater.

Until then I never understood parents, whose concern for their children's safety sometimes seamlessly transitions into an overwhelming rage. It is like walking on a Möbius strip all the way around to find your orientation suddenly reversed, though locally it is impossible to tell when and how your worriedness becomes frustration, or vice-versa.

I suppose I still have a hard time wrapping my head around the fact that emotions aren't discrete absolutes, which is just one example out of my many childish failings. What [the fuck] are you doing here,

I elided the cuss word, I was breathless with relief, all my anger disappeared. And I'm not saying it went somewhere else only to eventually return—I'm saying it was annihilated, just gone, as if I'd never felt it.

The funny thing is that it really did become cold. But for a while we sat in the dark, shivering. I could not tell whether he was crying or shivering or both. There were a couple square centimetres of warmth where our arms and legs were pressed together in the one chair; not enough, but I suppose neither of us wanted to move.

I'm going to say something that's going to be hard to hear.

Well, he was right about that. I'm so used to always choosing the easiest possible thing to say. And I never realised I was always going down the path of least resistance. I never realised how difficult it is to say anything of real consequence.

Maybe twenty yards away, a hapless freshman braced himself against a sapling and retched into the dirt. He coughed, and coughed, and coughed, but nothing came out.

For a crazy moment I wanted to take them both in my arms, bile and mucus and all, just to say:

EVERYTHING IS GOING TO BE ALRIGHT,

since lately, it's the only thing I can bear to believe in.

And that is precisely what does happen in my dream, before my very eyes, infinitely slowly, and a great yellowish cloud billows out and disperses, and where the sanatorium once stood there is merely a heap of powder-fine wood dust, like pollen.

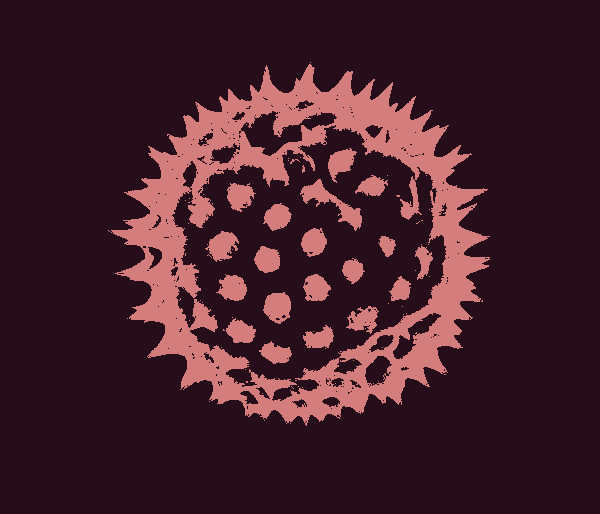

The pollen season has never been this bad.

We both remarked on the resemblance to sandstorms back home. Every time a car drove by, a thin skin of pollen lifted from its chassis and dispersed into the air, like a fleeing spirit. A coat of pollen covered my math homework.

Then it rained, and rivulets streamed down the sides of the asphalt, conveying vibrant yellow pollen. It looked like runoff from an industrial accident. We ate at an ice-creamery whose indoor air practically shimmered with sugar and the world outside was a scene right out of Chernobyl.

But the following morning saw the atmosphere as clear as ever. No more runny noses and gritty eyelids. The sewage system of the city of █████ must have been flooded with the grains, mindlessly produced by flowers for the sole purpose of sexual propagation. Traces of pollen were first found in the geological record dated around 400 million years ago, and since then levels of pollen on Earth have only increased, which perhaps is not a surprise, since there is nowhere else for it to go.

Every pollen grain, when observed under a magnifying glass, admits a frighteningly detailed texture of radial spikes, urchin-like. The grain's walls are made of a substance called sporopollenin, an incredibly robust and inert polymer with a subtle structuring unique to every species of plant, as if the grains themselves had evolved to be examined and recorded by dutiful archaebotanists and palynologists alike, disintered from the soil after the passage of eras. Each one of them seems to say, I was here, and then I could have been a flower, though if that truly were the case, the Earth would likely be suffocated in a terrible verdor.

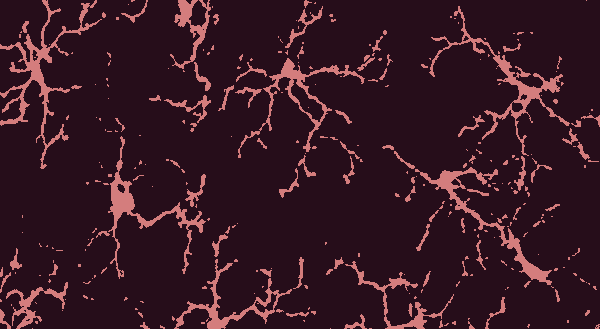

S has spent better parts of days looking through microscopes, and then looking at microscopical images on a computer screen. The images are immense and bring the program used to open them to a glacial standstill. The CPU churns. When they finally appear they are indistinguishable from pictures taken in a space observatory, a spray of luminous bodies against a black backdrop. But in reality they are pictures of slices taken from mice brains. The process of taking these paper-thin slices of tissue is also an intricate one, involving a glorified deli meat slicer and miserably cold hands. They are so delicate, you must use a paintbrush to maneuvre them onto the glass mount.

He patiently explains to me the configuration of neurons displayed in each photo, stained according to their type. There is a build-up of amyloid plaques, the sedimentation of proteins which leads to a condition called amyloidosis. Amyloidosis in general is a ghost-illness; its symptoms are vague enough to evade proper diagnosis until it's too late. But amyloidosis in the brain is most commonly associated with Alzheimer's, and the extracellular congestion which physically impedes the free-flow of your thoughts, eventually causing neuron death. Then there are the astrocytes, because they look like stars. And finally the microglia, which are really much smaller than their peers, and so numerous that their glowing red forms constitute a faint mesh of the entire brain section, about as substantial as the egg in egg drop soup.

I see it repeated over and over again in the brain cells of these mice, which live what you could call strange lives in the confines of a university research center: the quincunx in vitro, shining magenta, then green, then red, with every click of the cursor.