harmony-lessons

Уроки гармоннии/Асланның сабақтары/Aslannyñ sabaqtary

It is my tacit belief that Harmony Lessons is one of the best movies of the twenty-first century. In this post, I seek to make this not-so-tacit. Funnily enough, it is not that far from the lineage of man in the room movies I mentioned in my review

of First Reformed. Only, this time, it is more of a boy in the room.

Similarly to my post on First Reformed, though, I'll try my best to keep from describing too much of the movie itself. Because first, that's boring, and you could just go watch it. And second, I want to spoil as little as I can for you. Near the end of this post, I will be talking about the final scene; you'll know it when you see it. I'd recommend not reading that part until after you've watched, unless you don't plan on watching (anytime soon). Then, by all means, go ahead.

Harmony Lessons is a story of a boy, Aslan (played by Timur Aidarbekov), who is forced into reckoning his own impotence. He absorbs the petty trickle-down violence of his world so that his only remaining mode of outward expression is this very violence, transmuted by the strange organism of himself.

Sound familiar?

But not to worry: I won't be rehashing much of my last movie post, since Harmony Lesson's core novelty lies in the fact that it was created in Kazakhstan by a Kazakh director, with Kazakh actors—most, if not all of them without much professional experience. So, it is as far removed from the context of American malaise as possible. Thank god, I might hear some of you say. I was so sick of that garbage.

The shadow that lies across the background of this movie is not the Vietnam War, not the Iraq War, nor fossil fuel lobbyists, but the fall of the Soviet Union and the following political/economic curdling of Central Asia. In Russian, it is распад, which also means decay. It is notable that while most of the movie is in Kazakh (and seriously, what a beautiful language it is, as distant from Russian as it is to English), the only instance of spoken Russian is from the school nurse who administers the routine physical examinations to the students. It is during these examinations that the inciting incident occurs: Aslan suffers a humiliation which triggers the Rube Goldberg machine of the movie, as unwieldy, hulking, and unreadable as an analog computer.

It isn't surprising that foreign (not only English-language, but in general non-Kazakh) reviews can't help but comment on the otherness that permeates this movie at every level, down to the physiognomy of the actors. Here's an amusing snippet from the Hollywood Reporter:

The faces of the Central Asian teens are so unconventionally attractive that their sharp features and piercing dark eyes lend intensity to the characters, particularly in moments of introspection or malevolence.

I watched this with a browser extension that provides subtitles in various languages. Though the movie is primarily in Kazakh, there are hard-coded Russian subtitles, the default YouTube subtitles are given in Turkish, and the extension sputtered what it could make out in English (to be fair, it was surprisingly coherent). I kept getting distracted thinking how cool it was to notice resemblances between Kazakh and Turkish; they're in the same family, after all. These languages clamored on the screen and in my mind at any given time—and finally, the essay-review that I'll be referencing is written in Korean. What a mess. Indeed, part of the reason I've decided to write this is so that I can have a single text to refer back (and perhaps add on) to when thinking of this movie, without having to branch so much across time, language, and medium.

Though Harmony Lessons won the prestigious Silver Bear (for Outstanding Artistic Contribution) at the 2013 Berlinale, it still seems to be relatively obscure—at least, I know several people who have watched First Reformed and exactly zero who have watched Harmony Lessons...

I forget how exactly I stumbled onto it, though it was basically inevitable that I did, given my self-professed fascination with Kazakhstan. Their contemporary media industry has a lot to offer. Some of their biggest names in popular culture are the rapper Skryptonite, the pop group A-Studio, the Olympic figure skater Denis Yurievich Ten (rest in peace...), singer Dimash Qudaibergen and our director Emir Baigazin, a total wunderkind at the time of this movie's release; he was not even thirty years old when he took the prize home, the first Central Asian director to have ever won.

And rightfully so! If it were up to me, he'd have the Silver Bear! Even the Golden Bear, damn it!

In English and Russian (and even in Korean), the movie's title is Harmony Lessons

, but in Baigazin's native Kazakh, it is Aslan's Lessons

. Now that Kazakhstan has transitioned to the Latin alphabet, I can write: Aslannyñ sabaqtary. Aslan being an ancient Turkic name meaning lion

, the irony of which will not be lost on you. Sabaqtary coming from the Proto-Semitic consonantal root of s-b-q, which relates to precession, as in precedence.

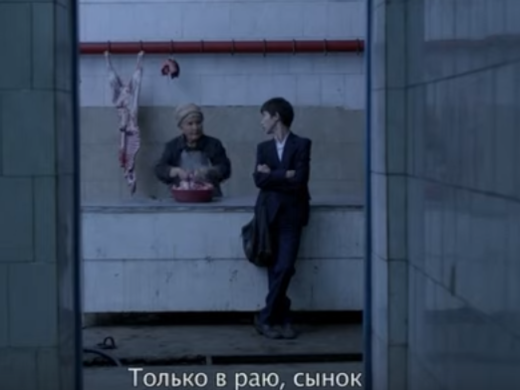

In one of a few scenes with his grandmother, Aslan, our lion, asks:

I'm sorry to even include these terrible-quality images (which are also quite cropped—don't worry, this isn't the actual aspect ratio of the movie), but I liked the dialogue too much to leave it out. Also, we see the emblematic way that Baigazin frames his subjects. We often see Aslan through a doorway, beyond a threshold, fenced in by cramped architecture. This is just another way the cruelty of the world infringes upon him. Yet just as often we see him in wilderness, under the dizzying height of telephone wires in a backdrop otherwise devoid of the trappings of civilization.

I mentioned violence at the start; in some ways, Aslan seems to be a tuning fork or talisman upon which violence is inflicted, and which a law of conservation requires that he redirect. Withdrawn yet studious and perhaps even brilliant, he takes to conducting scientific experiments on frogs and bugs he catches in his house. In one scene, he fashions an electric chair out of wire with which he condemns a cockroach to the death penalty, for the crime of existing. He spends hours in the bathroom, obsessing over cleanliness and pouring steaming water on himself from a kettle. He performs the exercise shown to him at the traumatic physical examination, staring at himself in the mirror and touching his nose with alternating hands, arms outstretched and parallel in front of him.

Most of all, he plans his revenge on the boy who had humiliated him in the first place; a petty thug by the name of Bolat.

All camera movements and compositions are tightly restrained from the moment the film begins: the opening shot is of a rice paddy which bifurcates the screen into blue sky and green grass. We see Aslan walking into frame, a thin and dark figure now introducing a vertical split.

Some of the most memorable shots to me are those that depict the bleakness of the Kazakh countryside, the silence of Aslan's senescent household, the still bodies & faces of students in bored stasis or rigid fear.

Russian director Andrei Zvyagintsev depicts a similar end-of-history flatness in his critically acclaimed Leviathan (which came out just a year after Harmony Lessons), where corruption has so thoroughly riddled all governmental and religious institutions that it seems to have become almost a faceless force of nature, an insensate and eschatological punishment on the scale of Job's. This virulence was once an infection, a symptom. Now, it is simply all that remains.

But at least in Harmony Lessons, there is the opportunity for paradise. Two, actually. One is straight out of a Brothers Grimm fairytale, an arcade in the heart of the city where Aslan and his friend Mursayan (a fellow pariah who comes from the city, and whose stylish appearance belies his urban upbringing) can play to their heart's content, shedding the ugliness of their home, entering a world of garish color, light, and noise. The second paradise is revealed in the very last scene.

Spoilers begin here.

This ending shot echoes the first: two bands of blue and green, only there is another separation this time, one between ground and water. This bookending lends a powerful symmetry to the movie, giving it a structure far older than filmmaking itself: the triptych, maybe, or the repeated antiphons of funeral dirges.

Inexplicably, Mursayan and Bolat call out to Aslan across a lake. (Here, the Korean essay makes reference to perhaps the most iconic use of the reflective surface of water in film, that of Ivan's Childhood, directed by Andrei Tarkovsky.)

They yell and wave their arms:

Aslan, come on, we're here. Come to us. Walk on the water, don't be scared.

But Aslan's back is turned to us, as in the beginning. Unlike the beginning, though, he is shirtless and pale, white where he was once black. Sunlight limns his thin shoulders; he looks like a frail Adam surveying his Eden. Waterside bugs sing loudly in our ears. We can only imagine the expression on his face as he looks out at the other two boys, each of their presences an utter impossibility.

Would it be hate, or sadness, or perhaps relief? Somehow, I can't imagine Aslan wearing any of these, maybe because I can't imagine them on me—and in my hopeless self-indulgence, I've come to view Aslan partly as a fugitive piece of myself, one of my potential pasts and futures seen as in a mirror, darkly.

We see it in the very beginning, as Aslan chases a sheep around his family's yard and we are treated to the methodical, gory, and interminable process of slaughter, skinning, and gutting. Nothing is wasted; whether Aslan has killed a fellow boy, a cockroach, or a farm animal, it turns out that everything is its own permutation, returning to him in its own slow but inevitable arc. How else would Mursayan and Bolat be calling to him under this perfect sun, under a sky so blue? How could his tormentor and his ally be standing shoulder to shoulder? And how else could the sheep be dancing across the surface of the water (a figure that could not be more Christ-like if Baigazin had slapped a crown of thorns onto it and given it stigmata)?

Because in this world nothing is truly lost nor truly found. Yes, it is a world in which all that is solid melts into air

, and yet something—an ergodic principle, a logos, a perfect sky and the screaming of summertime insects—ensures that even if it takes a million years, this very air condenses back into tangibility. It makes sense that the ghost of a fallen superpower would take decades to dissipate, its former heft now a damning inertia, a heaviness in the lungs of its orphans, the relentless & hypoxic vacuum of lack. Только в раю, сынок, his grandmother responds. Only in paradise. Well, he's there now.

Aslan gets to his feet. Will he walk across the water to join them, or will he sink and drown?

Are you listening? Aslan, step on the water...