deskilling

Sometime in the summer, I found out that William Langewiesche, one of the

best nonfiction writers in America, had died via the Recent deaths

listed on the front page of

Wikipedia. I spent the next few hours reading his commentaries on airplane

crashes, shuffling from the crowded gate to a middle seat on a JetBlue

plane, my phone set on the lowest brightness as if I were reading smut

instead of an autopsy of EgyptAir Flight

990.

listed on the front page of

Wikipedia. I spent the next few hours reading his commentaries on airplane

crashes, shuffling from the crowded gate to a middle seat on a JetBlue

plane, my phone set on the lowest brightness as if I were reading smut

instead of an autopsy of EgyptAir Flight

990.

Langewiesche was the son of a pilot and had trained to become a pilot

himself before even entering college. In his incipient professional years,

those he called the wilderness

, he was a writer who got nothing

published, and so supported himself by flying planes. His later essays,

often touching on aviation disasters, are some of the finest examples of

modern American nonfiction. They provide a unique specialist's

commentary marked by a controlled build-up of tension, black humor, and a

soft, but persistent and probing pressure on the pathologies of his field.

The through-line of his working life was a focus on the ways in which human

error could propagate through systems intended to be immune to those exact

errors.

When I first came across the word deskill

, I thought it came from the

words desk

and kill

bolted together, a reference to the act of

writing (at a desk) being painful and involving some kind of (metaphorical)

murderous force. I later saw it in Langewiesche's 2014 article about the

crash of Air France Flight 447, The

Human Factor, in which I finally learned its definition, but it was only

when I started writing this post that I caught onto its proper prosody:

de-skill

, as in the disappearance of skill, or of skill's value.

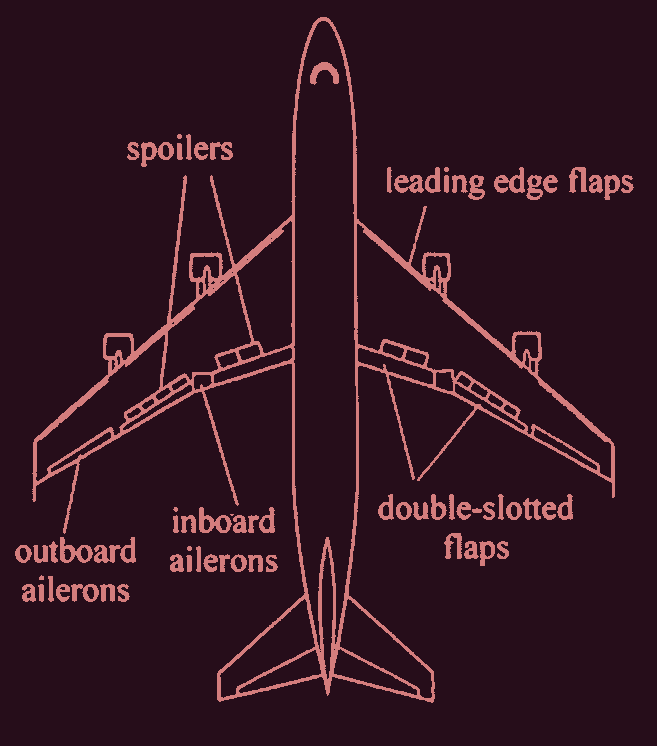

Langewiesche lived through the takeover of fly-by-wire controls in commercial aircrafts in the late eighties. Fly-by-wire promised a new kind of nervous system for airplanes. Before, the interface between an airplane's flight and its pilots' inputs was a mechanical one, governed by the teamwork of simple machines found in any introductory physics course: pulleys, screws, wedges, etc. This in theory dictates a one-to-one correspondence between the action of a pilot and the resulting change in the control surfaces of the aircraft, which include the ailerons, elevator, and rudder. I say correspondence because the relationship goes the other way: external aerodynamic forces acting on the plane have an equal effect on the controls. This enables pilots to receive immediate tactile feedback from their environment, but makes it difficult for them to transmit the necessary force to maintain control over their aircraft. Most critically, the increase in aircraft size, power, and speed also came with an increase in the complexity and weight of the flight control system.

Fly-by-wire sought to solve the unwieldiness of the mechanical flight control system with a streamlined and computerized interface. Any manual input on the pilots' part was now translated into an electronic signal and sent to a central flight control computer, which then calculated and carried out the adjustments required for the aircraft to achieve the desired position. The computer could use real-time data from its own sensors to fine-tune any given manual input, confined in a feedback loop intended to reduce or eliminate the margin of human error. With advancements in autopilots, this feedback loop often did not require any human intervention at all.

From the other direction, pilots became fundamentally disconnected from any forces acting on the control surfaces. What was once a consequence of basic mechanics became a problem at the forefront of control engineering, since it was now up to the control system to generate artificial forces in order to simulate the tactile feedback naturally occurring in mechanical systems. Also, mechanical systems tended to fail piecemeal in terms of components, but fly-by-wire systems were prone to total failure: for as soon as the central flight control computer malfunctioned, all input and output between the pilots and their machine became meaningless.

It is fair to say that fly-by-wire was a net positive for the commercial aviation industry. It enabled safer, stabler, and longer flights—in other words, without fly-by-wire, the aviation industry as we know it today would not exist. But to people like Langewiesche, and Nadine Sarter, an industrial and operations engineer whom Langewiesche cites extensively, such advances have taken on the flavor of a Faustian bargain.

The problem is that beneath the surface simplicity of glass cockpits, and the ease of fly-by-wire control, the designs are in fact bewilderingly baroque—all the more so because most functions lie beyond view. Pilots can get confused to an extent they never would have in more basic airplanes.

If fly-by-wire systems enable the automation of everything that is routine,

which by definition takes up the vast majority of flight experience for

pilots, then the rare but critical instances of unpredictable, faulty

behavior become ever more difficult to prepare for, by the very nature of

their unusualness. In Langewiesche's words: flying becomes … a

mind-numbing wait for the next hotel.

Put another way, pilots can

accumulate hundreds of hours of flight experience over a year, but have done

actual piloting for only a handful of those hours. Because flying an

aircraft demands less and less from pilots, there are presumably pilots

working today who might have not been able to work in an older era with

higher standards. Langewiesche describes it as a spiral in which poor

human performance begets automation, which worsens human performance, which

begets increasing automation

. Does this sound familiar?

Later on, there's a great piece of snark from Langewiesche, in response to a Boeing avionics engineer (I'm not sure it was meant to be snark, but it sure does sound pointed to me):

From the design point of view, we really worry about the tasks we ask them to do just occasionally.

I said,Like fly the airplane?

You could imagine the exchange being about any career whose drudgery has been, or is in the process of being automated away:

like write code?

,like know a foreign language?

,like write college essays?

,like make a pitch deck?

, and,like record the minutes of this morning's meeting?

Flying is only a special case Aviation turns out not to be so exotic after all, since a similar phenomenon has been taking place in household garages. We don't have to go all the way to self-driving cars to recognize that the computers in cars today are more complex, unreadable, and impenetrable to the layman than ever. because the potential risk posed by an unprepared pilot far outweighs any consequences related to the above examples (maybe except for the coding). However, whether the effects of deskilling are acute (fatal plane crash, critical data breach) or distributed across time and population (erosion of employee bargaining power), they are unequivocally negative.

Automation allows students and workers to bypass grunt-work and tedium, but

this shift in the scope and hierarchy of work will necessarily lead to

deskilling. Sometimes it's worth it (e.g., manual data entry is a dying

career, and it will not be missed), but other times the consequences of the

great hollowing-out of expertise, however outdated that notion of expertise

might be, are catastrophic. Even when the stakes are lower, such as in the

case of white-collar knowledge workers

whose gruntwork consists of

things like summarising meetings, such tasks still provide important

training for the intern or entry-level employee, training which has been

completely co-opted by glorified chatbots. In this way, deskilling infects

both experienced workers and novitiates. Experienced workers are

incentivized to let their skills atrophy over time, while novices are

not given even the opportunity to acquire the skills they need to

advance in their careers.

To make matters messier, the responsibility of resisting deskilling falls not onto the companies that provide such automation, but onto the people that use the tools. However, with zero financial incentive (in fact, all incentives point towards taking the easy way out, since automation is only improving), it is hard to see a widespread and standardized campaign with the aim to preserve or pass down the skills that once defined competency in a field.

It is fine, even good, if a field changes dramatically. After all, computer

programmers have long since abandoned the punch cards of the seventies, and

there is no reason to return to such a limited medium. Langewiesche deems

the engineers behind modern avionics systems as some of the greatest

unheralded heroes of our time

, and I can't disagree: in terms of safety,

the numbers speak for themselves. I wouldn't want to fly in a

pre-fly-by-wire world. And I don't want to be guilty of the same utopian

thinking of profit-motive technocrats, cast in reverse. Blindly clutching

onto older standards and protocols for the sake of lionizing the past is

just as pernicious as focusing only on future growth.

But deskilling impacts capabilities that are still required for the

safe operation of our current-day, deeply complex systems, systems that

cannot be contained neatly inside any single specialist's brain. Deskilling

is ultimately a kind of forgetting, and soon enough our refusal to remember

will come back to haunt us. When a global decline becomes impossible for

even those at the peak to ignore, the predominant emotion may not be fear or

grief, but an all-around confusion, a dumb befuddlement: how did we even

get here?

(for instance, daliwali writes here that government

collapse is likely to happen via gradual demoralization rather than a

singular violent coup.) Deskilling sits at the necrotic heart of the competency

crisis. It seems we are burning the rungs of the ladder we are climbing

as soon as we pass them, and you can imagine where that will lead us. Soon

enough, we won't even have to imagine.

Rest in peace William Langewiesche, 12/06/1955—15/06/2025. For more information about the history of fly-by-wire systems as well as in-flight simulators, refer to the aptly-titled In-Flight Simulators and Fly-by-Wire/Light Demonstrators by Peter G. Hamel. For such a niche subject, it is a surprisingly accessible read. For a selected list of Langewiesche's works, refer to the one made by longform.org. For an essay on why Western countries are failing to produce skilled workers, refer to H-1Bs by baazaa, who manages to describe all the moving parts of deskilling in detail without ever once using the word.