20(21 | 22 | 23 | 24)

Augmented nonfiction

Thu, 27 Jun 2024 20:41:21 | [standalone]

These three books, in order, run the spectrum from historical fiction to dramatized nonfiction.

- Pafko At The Wall/Underworld by Don DeLillo

There is the secret of the bomb and there are the secrets that the bomb inspires, things even the Director cannot guess—a man whose own sequestered heart holds every festering secret in the Western world —because these plots are only now evolving. This is what he knows, that the genius of the bomb is printed not only in its physics of particles and rays but in the occasion it creates for new secrets. For every atmospheric blast, every glimpse we get of the bared force of nature, that weird peeled eyeball exploding over the desert—for every one of these he reckons a hundred plots go underground, to spawn and skein.

- When We Cease to Understand the World by Benjamin Labatut

Among the few possessions Fritz Haber had with him when he died was a letter written to his wife. In it, he confessed that he felt an unbearable guilt; not for the part he had played, directly or indirectly, in the death of untold human beings, but because his method of extracting nitrogen from the air had so altered the natural equilibrium of the planet that he feared the world’s future belonged not to mankind but to plants, as all that was needed was a drop in population to pre-modern levels for just a few decades to allow them to grow without limit, taking advantage of the excess nutrients humanity had bestowed upon them to spread out across the earth and cover it completely, suffocating all forms of life beneath a terrible verdure.

- Helgoland by Carlo Rovelli

At first, I was deeply alarmed. I had the feeling that I had gone beyond the surface of things and was beginning to see a strangely beautiful interior, and felt dizzy at the thought that now I had to investigate this wealth of mathematical structures that Nature had so generously spread out before me.

Nothing is like the emotion of seeing a mathematical law behind the disorder of appearances.

I’ve become really interested in what I foolishly call “augmented nonfiction”. I think this interest stems from my fascination with medical thrillers from two-three years ago, but I’ve generalized it since. I loved the way these narratives wavered between “this happened, but I’m writing it in a more exciting way” and “this happened exactly as I wrote it, and it’s more exciting than anything I could ever come up with”.

When We Cease To Understand The World also has a story which features Alexander Grothendieck. I’m convinced that reading it, in some obscure way, nudged me towards my life today. Labatut wrote that Grothendieck and Mochizuki glimpsed “the heart of the heart”, and what they saw forever changed them. It creeped me out a little; one of my mutuals on Neocities calls himself holyheart, and his tribulations regarding Hartshorne’s Algebraic Geometry form the crown jewel of his website. Grothendieck was a pioneer of algebraic geometry. What a weird coincidence, unless I’m missing something.

Every six months or so I will make an account on Reddit to ask a question, linger for a week, and then delete it right after. This time I created an account to ask about this not-genre. What other books are there that weave together fiction and nonfiction in such a seamless way? I could only think of Sebald and his walks through Europe, his every step treading through a stratum of history.

Excerpts from Why Johnny Can't Add

Sun, 16 Jun 2024 15:44:29 -0400

Knowing is doing. In mathematics, knowledge of any value is never possession of information, but “know-how”. To know mathematics means to be able to do mathematics; to use mathematical language with some fluency, to do problems, to criticize arguments, to find proofs and, what may be the most important activity, to recognize a mathematical concept in, or to extract it from, a given concrete situation.

The object of mathematical rigor is to sanction and legitimize the conquests of intuition, and there was never any other object for it.

These two quotes are some of many that lingered in my brain after reading Professor Morris Kline’s Why Johnny Can’t Add: The Failure of New Math. I can’t offer much commentary on his pedagogical criticisms because I have no experience teaching math and was definitely not alive around when New Math was being implemented in American curriculums.

The first quote seems to warn against premature generalizations and abstractions. The vagaries of theory should follow after one is accustomed to the concrete and the algorithmic—not the other way around. Also, one shouldn’t expect that the passive intake of information, whether it is reading textbooks, or listening to lectures, can lead to any substantial understanding, much less mastery of any given concept.

As for the second quote, I just liked it. It’s a strong statement: mathematics somehow acting as both the schoolmarm and handmaiden of intuition.

Traveling to Korea

Sat, 25 May 2024 18:10:10 -0400

After some hemming and hawwing about what I’m going to do for the rest of my summer after my research program, I’ve decided that I’m going to Korea for two weeks with my boyfriend. (Interestingly enough, there is a “Little Russia” in the city, so I might be able to practice some Russian speaking after all…? In Korea, of all places.) It’s strange to have been born in a country, to officially be a citizen of it, and yet to look at it through a tourist’s eyes – I haven’t actually lived there for almost a decade now. It’s only now, making this itinerary, that I have bothered to properly learn the topology of my hometown, which is funny-sad. I’m going to make for an awful tour guide.

Before traveling I always rewatch at least a part of Sans Soleil, the movie-essay directed by Chris Marker. It’s one of my favorite movies ever; I remember watching it during the 2020 quarantine, transfixed by the droning narration, the gentle persistence of its pacing, and the somnolent vignettes of countries and their inhabitants, of lives long gone. And most of all, the commutes. Subways, cars, buses, boats, etc. It’s the kind of movie that makes you think it’s raining outside, even though you live in the desert.

I remember on the front page of my website, I used to have a quote from one of Marker’s writings in Le Depays:

No one knows exactly what to do with this in-between, this twilight zone, this nameless realm shared between the eight hundred and eight gods who watch over the flock of dreams, no one knows how to address it, but at least one can be polite.

I often read Neocities blogs written by expatriates, saddleblasters being one of them. And Vashti, from time to time, who writes about her planned travels. Their depictions of where they live and how they interact with their cities, whether it is disparaging or reverent, whether it is attending an experimental music performance or scans of a well-loved and -used sticker book are all of interest to me in a geotemporal context, because I honestly don’t think I’ve ever known a place or been comfortable inhabiting it. I went to an international school, so all my high school friends are scattered around the world. Even the friends I’ve made in college are flying to the other side of the country to grind out internships. Transience is ironically the only constant. In fact, it feels disingenuous to say I even have a hometown. It amounts to a GPS coordinate placed exactly over the hospital room in which I was born. Then, the ambient people and environment of my middle- and high-school years are mainly just that – ambient. In two years, I’ll be done with my undergraduate degree, and I’ll probably have to move someplace else… again.

I used to feel dissatisfied about this, but now I don’t think it’s really a good or bad thing, just a side-effect of modernity. I’ve been in the in-between for all my life, and I’ve never learned how to address it either, but it’s alright. I turned out alright, I should think.

Maybe after the trip I will have nice pictures to share with you all, and it won’t just be my rambling, which goes nowhere.

Mainly what comes to mind now when I think of Korea is a memory from when I must’ve been about 10 years old, or a bit younger. Maybe exactly a decade ago. I remember looking out the window of my grandmother’s house (we used to stay at her place for a few days when we visited Korea). It was twilight and cloudy, I think it was approaching winter. From the view of the window, the Hyundai Department Store was visible, its huge facade a glowering golden square against the encroaching dimness. I remember I was excited about Christmas, I remember thinking that the department store was an entire world to me, a sort of castle, a sort of temple. I never meant to let it into my long-term memory, but it happened anyway.

Quick April update

Sat, 27 Apr 2024 19:25:33 -0400

Where have I been for the past two months?

I don’t have a good answer to this. Instead, let me talk about my second year of college.

I admit that it could’ve gone a lot better. I’m still very withdrawn and whenever I’m not in classes or talking to my few friends (which must be at least 3/4ths of an average day) I’m spending time with myself. Midway through freshman year, I met a Master’s student who kept insisting that I shouldn’t “procrastinate on life”.

And I nodded and took it to heart… and then I spent the next year doing just that. At least, that’s what I feel like has happened.

Don’t get me wrong—I’m still “doing things”, i.e. passing all my classes, studying, doing just enough socially so that I’m not a total shut-in (though I’m precariously close), doing like one extracurricular activity consistently.

But sometimes I get sick of skimming the surface all the time. I want to actively participate in life instead of sitting there, doing the bare minimum.

The midpoint of your college tenure seems to be the point at which you have to start taking shit seriously. At least, more and more people expect me to know what I want to do with my life. And I do know: I want to learn, I want to write, I want to create things.

But I need a real answer, and quick. Something that makes more sense, like “becoming a teacher” or “web developer” (can’t complain), or even “going to grad school”.

On paper my life looks just fine, but in reality I have no idea what the hell I’m doing, and this is far more terrifying than exciting to a person like me. I feel unable to do anything about it.

"...the desire to be dead rather than to live"

Sun, 18 Feb 2024 21:04:02 -0500

Excerpt from Herodotus, The Histories

[7.44] When Xerxes had come to Abydus, he had a desire to see all the army; and there had been made purposely for him beforehand upon a hill in this place a raised seat of white stone, which the people of Abydus had built at the command of the king given beforehand. There he took his seat, and looking down upon the shore he gazed both upon the land-army and the ships; and gazing upon them he had a longing to see a contest take place between the ships; and when it had taken place and the Phoenicians of Sidon were victorious, he was delighted both with the contest and with the whole armament.

[7.45] And seeing all the Hellespont covered over with the ships, and all the shores and the plains of Abydus full of men, then Xerxes pronounced himself a happy man, and after that he fell to weeping.

[7.46] Artabanus his uncle therefore perceiving him […] having observed that Xerxes wept, asked as follows: “O king, how far different from one another are the things which thou hast done now and a short while before now! for having pronounced thyself a happy man, thou art now shedding tears.”

He said: “Yea, for after I had reckoned up, it came into my mind to feel pity at the thought how brief was the whole life of man, seeing that of these multitudes not one will be alive when a hundred years have gone by.”

Artabanus then made answer and said: “To another evil more pitiful than this we are made subject in the course of our life; for in the period of life, short as it is, no man, either of these here or of others, is made by nature so happy, that there will not come to him many times, and not once only, the desire to be dead rather than to live.”

I want to do math

Fri, 02 Feb 2024 19:59:16 -0500

I haven’t made you all privy to what I think is one of the biggest revelations I’ve ever had in my life, in large part because it just seems so absurd and even a little embarassing. Said revelation:

I want to do math.

“Okay,” you might be thinking. “She’s gone truly insane after all.” Which is a fair thing to think, honestly. I also am struck by how silly it sounds. It’s made even sillier by a few facts:

- I, currently, am not good at math (whatever that means).

- I’ve never been good at math/it’s never come really intuitively to me. I did terribly in Calculus I and Calculus II was better, but still a slog.

- A lot of it isn’t really applicable to the practical things that I need to do in life.

In a sense, it’s a pipe dream or a quarter-life crisis. In another, more pernicious sense, it feels like a selfish endeavor. I’ve long been fascinated by “mathematicians”—those who love math and those who do math as their profession (and of course, the generous intersection of the two), and perhaps even envious of the all-encompassing passion they have for something so abstract. But for my entire life, I’ve always thought that that could never be me, because I’ve never done competitive math, or participated in Olympiads, or even done competitive programming. For much of middle and high school, I thought I disliked math, to put it lightly, and my family and I pretty much took it for granted that I just wasn’t a “math person” (again, whatever that means).

How I wish I could go back in time, shake my 15-year old self by the shoulders, and tell her that there was no real reason that she couldn’t do it! To stop making excuses!

Of course, I harbor no delusions of grandeur. I’m not going to go into math academia, and I certainly don’t expect to. But I want to learn more of it, and I’m more sure of this than I have been of anything else in my life. Not to sound incredibly pretentious and deranged, but it really does feel as rigorous and closest to a notion of “truth” as anything I’ve ever studied (as painful as the problem sets can be).

P.S.: I’m still learning programming language theory when I can. It ties in a lot with math, as expected! I will make another post about it when I get some breaks between my assignments, because it’s incredibly cool stuff. (Or at least, I think it is).

I also went to an introductory talk on Category Theory today with a friend who is also interested in math! It was fantastic and led by an insanely knowledgeable undergrad. Now I know what functors and morphisms are and my world is just that little bit bigger for it.

Listening to music and jailbreaking a Kindle

Sat, 06 Jan 2024 23:33:34

It was raining heavily almost all day today, so I ended up staying indoors, listening to music and reading, which are the two things this entry is all about.

On David Berman

It was recently David Berman’s birthday (4th of January). Berman

was the lead singer of a band called Silver Jews back in the 90s and

2000s. Berman, and Pavement members Bob Nastanovich and Stephen Malkmus

were all friends, though Silver Jews never got near as famous as

Pavement did. Not that Berman minded; he named his band Silver Jews

on purpose so that people would be dissuaded from even bringing them up

in conversation. One of the only live concerts he ever played as the Jews (and

the last) was inside a cave in Tennessee, before he virtually disappeared for a

decade.

Silver Jews split up in 2009 and after a long hiatus Berman started a solo project by the name of Purple Mountains, before committing suicide in August 2019. His new self-titled album had just come out July of that year. In my opinion, he wrote some of the funniest and most beautiful lyrics ever to be sung to a tune. He had always considered himself more of a poet than a songwriter or singer.

Here’s one of my favorite verses from him, from a track called The Frontier Index from the album The Natural Bridge:

Boy wants a car from his dad

Dad says, “First, you got to cut that hair”

Boy says, “Hey, Dad, Jesus had long hair”

And Dad says, “That’s right, son, Jesus walked everywhere”

I dunno, it just makes me smile every time I think about it, especially hearing it in his very monotone singing voice.

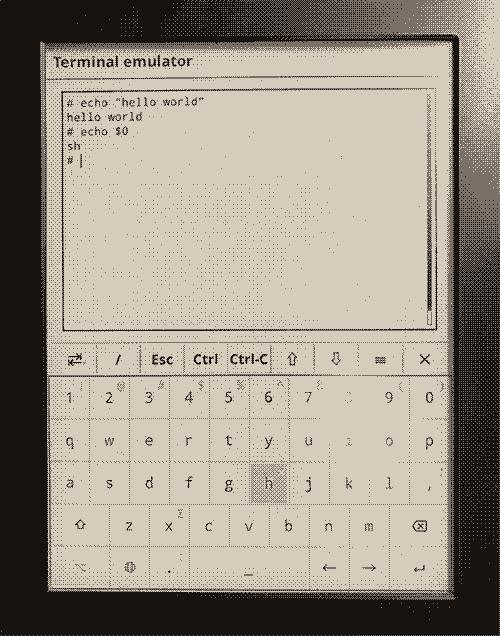

On Dostoyevsky and jailbreaking the Kindle Paperwhite

This semester, I’m going to be taking a class where we basically read The Brothers Karamazov to within an inch of its life, so I figured that I could get a head start on it. I’m 20% of the way through, on the Pevear & Volokohnsky translation (not the translation that we’re reading in class, but it’ll be interesting to compare the two).

Also, turns out it is pretty easy to jailbreak a Kindle, at least the one I have, which is the 2013 Paperwhite (abbreviated as PW or PW1).

There’s a forum full of meticulous and dedicated Kindle software/hack

developers who have put up an extremely detailed guide

on jailbreaking, as well as many extensions, like the ability to have a

custom screensaver. The jailbreaking process itself is quick and simple:

just unzip-ing and mv-ing files from your

computer to your Kindle over USB.

To literally no-one’s surprise, the Kindle OS is based off the Linux kernel and the document viewer I installed, called KOReader, lets you interact with a tty.

This means you can run htop, interact with systemd, and

ssh into your Kindle, which is really amusing to me for some reason.

You also have access to the entire filesystem, as well as the ability to load in custom dictionary files (like StarDict files) for many languages. Apparently there are options to have RSS readers and an FTP server? Point is, it’s quite extensible, and anyone familiar with UNIX systems will definitely feel at home.

As expected of a FOSS program, you have a lot more control over customizing various viewing/typesetting options, but I’d say the defaults are very sensible. Also, I’m fairly sure that for the original Kindle PW, there was no dark mode at all, but KOReader gives you access to it. Not really sure why you would want dark mode on e-ink, but I guess it’s nice to have as an option.